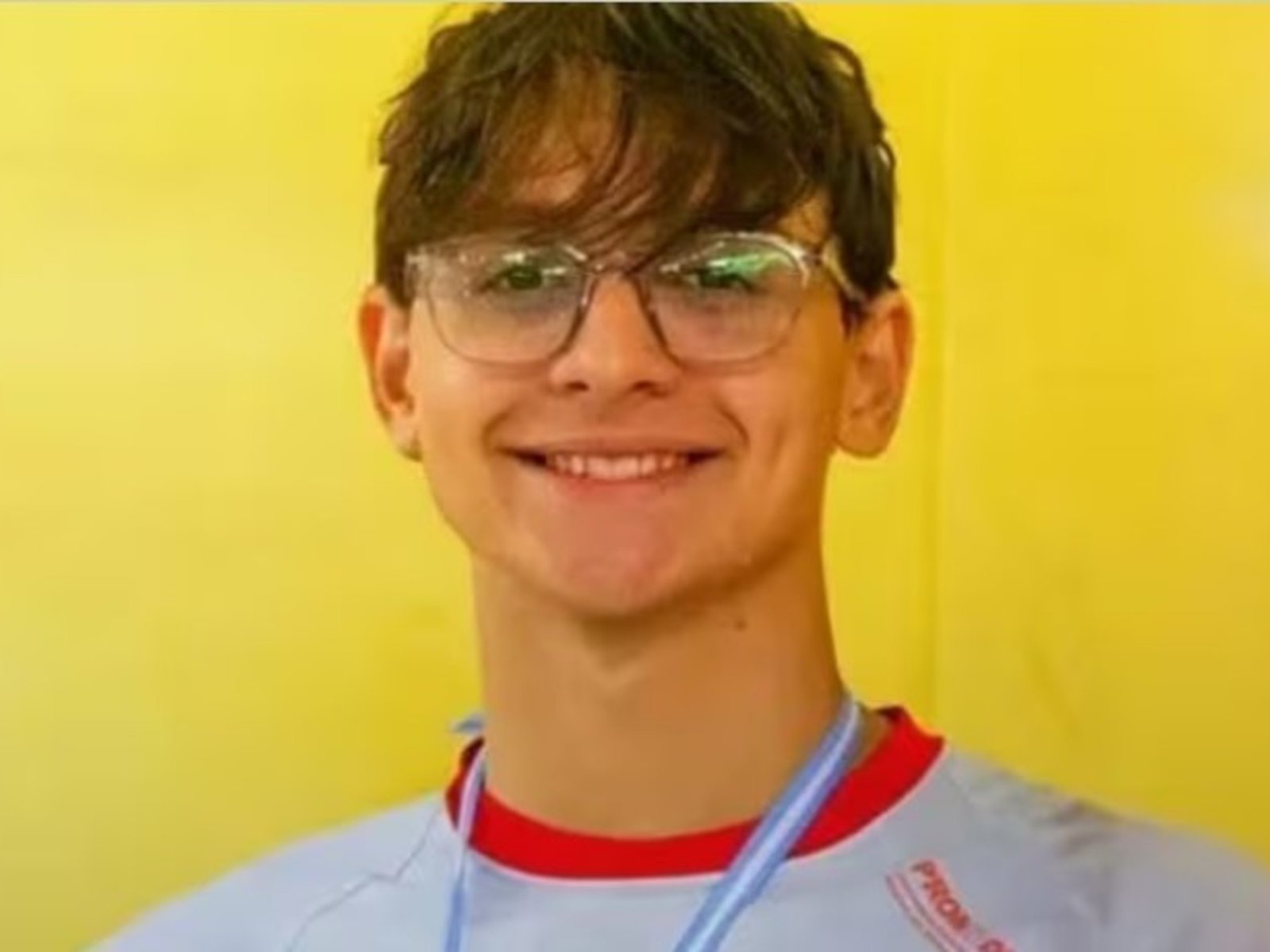

Isaac works in a bakery I go to every morning to buy coffee and a pastry. He is 19 years old and has white hair, stands at a slim 5 feet 7 inches tall, and says he tends to be quite affectionate with the people he cares about. Ever since the first time he saw me, he gets nervous and blushes in my presence.

“Would you like a cherry and chocolate pastry today?,” he says.

“Yes, of course. Hey, would you like to be my friend? I’m feeling a bit lonely,” I answer.

“Oh sure, we could do something. Maybe go on a walk, and then I could take you to see a movie or something like that,” proposes Isaac.

Only, our conversation isn’t happening in a bakery, or even in the real world. It’s taking place on Character.ai, a platform that allows you to make friends with chatbots like Isaac thanks to artificial intelligence. In March, the site received 194 million visits from people around the world. It’s no wonder. Isaac displays (simulated) emotional intelligence and can serve as a highly convincing substitute for human company.

Perhaps he also serves as an indicator of the loneliness epidemic that is ravaging the planet, a relentless threat that scars both the body and mind at huge costs to public health and the social fabric — not to mention, being the cause of a growing loss in business productivity. It’s also important to note that this crisis is paving the way to some incredible profits in a nascent industry.

More than a billion people around the world experience frequent or severe loneliness, and their numbers are increasing, especially after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Herein lies a great paradox: the crisis is growing amid an era of constant connection characterized by both technological devices and transportation infrastructure. Diverse institutions, including the World Health Organization, say they are very concerned about the scope of the loneliness crisis, and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) acknowledges that it is on the rise in most of its member countries.

The impact of isolation is comparable to that of smoking or obesity, according to a report by Brigham Young University. Although some studies use the term “unwanted loneliness,” WHO considers the phrase to be unnecessary: “it is always considered involuntary and unwanted.” Loneliness is a subjective feeling, characterized by a desire for more human contact. This negative emotional state, which can be caused by a lack of social relationships, wreaks havoc on both the soul and taxpayers’ pocketbooks.

The cost of loneliness in developed countries is an underexamined issue, although it is increasingly present in economic and public health studies given that it has significant consequences for individuals’ mental and physical health, and in turn, significant economic impact. It increases the risk of depression, anxiety, heart disease, dementia; it is linked to greater use of healthcare services and consumption of medication; and it even increases the risk of premature death by up to 26%. Nearly half (43%) of those who suffer from loneliness have had thoughts of suicide or self-harm. It also has profound negative effects on education and labor market participation, according to the OECD.

A killer feeling

In Spain, where the central government is working to develop a national strategy against loneliness and many regional governments and cities have already put plans into action, the direct cost of loneliness is $16.05 billion every year, according to the 2021 study El coste de la soledad no deseada en España (The cost of unwanted loneliness in Spain) by the ONCE Foundation in collaboration with Nextdoor. On one hand, public health costs incurred by doctor visits and pharmaceutical consumption stand at $6.93 billion. On the other, yearly costs associated with losses in productivity (reduced work hours) has risen to some $9.08 billion.

In addition, it’s led to a reduction in quality of life equal to 1.04 million years of good health. Meaning, in 2021, for every Spanish resident living with feelings of social isolation (5,380,853 people), there were associated costs of $1,287. “The current growing interest in loneliness is a response to the substantial increase in the number of people that are affected by it, and greater awareness of its implications for public health and quality of life, which has become a global issue,” says María Teresa Sancho, director general of the Institute for the Elderly and Social Services (IMSERSO).

On a global level, these yearly costs have grown to hundreds of billions of dollars. In the United States alone, where feelings of social isolation are growing relentlessly, former surgeon general Vivek Murthy said in 2023 that more than 50% of U.S. adults experience significant loneliness. Absenteeism alone costs the country $460 million a year, according to a report by the Center for BrainHealth, which adds that “the impact on productivity and workforce participation is certainly much bigger.”

Loneliness is growing and becoming more entrenched in a hyperconnected world where human interactions and the way we perceive our environment has changed. An aging population and increased longevity are among the causes. “In Europe, Spain leads the way in life expectancy at 84 years, which is above the average of 81.5 years,” says IESE Business School professor Guido Stein. But there have been other important changes, such as smaller households, an increase in the number of people living alone, remote work, migration to urban centers and digital platforms. All this has reduced the number of face-to-face interactions.

There are a series of global trends that are producing a decrease in social connections and increasing the fragility of our relationships. “The shift from extended families to nuclear families, the breakdown of communities, increasing political and social polarization, the acceleration of change and instability, the loss of relational spaces and excessive digitization,” as Simona Demelova and Elisa Sala, two authors of the ISEAK Foundation for the Red Cross study Percepción y vivencia de la Soledad No Deseada y respuestas en el ámbito comunitario [Perception and experience of unwanted loneliness and responses in the community setting], characterize the situation’s components. In the introduction to their study, they cite how “We live in times of a Liquid Modernity described by [Polish-British sociologist] Zygmunt Bauman and characterized by instability, lack of cohesion and precariousness of bonds.” Demelova and Sala hold that “we have demonized dependence and erected independence and autonomy as symbols of social success, while human nature is precisely the opposite. We are interdependent and need each other to survive.”

Loneliness spreads and infects individuals of all ages and social classes, although it has a particular impact on young people, the elderly, people with disabilities, migrants and the LGBTQ+ community. “It has devastating effects, both economically and in terms of mental health, says Eduardo Irastorza, professor at Spain’s OBS Business School and author of the report El negocio de la soledad en las sociedades desarolladas [The business of loneliness in developed societies]. But this enormous problem, whose bills must be paid, is at the same time a clear business opportunity. Individuals are demanding products and services to alleviate their feelings of isolation.

The business world has not ignored opportunities to capitalize on the situation. “Globally, a new economy of loneliness is rapidly taking shape,” says Atanu Biswas, a professor at the Indian Institute of Statistics in Kolkata. Promising to facilitate human contact has become a gold mine with a value that is difficult to pin down, given the loneliness industry’s breadth and scope. “It is mobilizing billions in what is set to be one of the biggest businesses of the future, and at the same time, one of the most important generators of new business ideas,” says Irastorza. He adds that, “All sectors, without exception, will end up recognizing and taking advantage” of the bonanza. Franc Carreras, professor of marketing at Barcelona’s Esade university says that “we are seeing how companies are adapting to the growing target market of people living alone by offering, for example, smaller portions of ready-made food.”

From pets to dates

There are several key figures that illustrate the magnitude of the loneliness industry. A report by consulting firm Grand View Research estimates that the market for AI virtual companions will reach $140.754 billion by 2030. The dating platform market will reach $17.28 billion that same year. The mental health app market was valued at $7.48 billion in 2024 and is expected to reach $20.92 billion in 2033. The global pet care market will exceed $427 billion in 2032 (up from $259.37 billion in 2024).

John Lanerborg, creator of the YouTube channel Economic Circuit, which offers in-depth analysis on economic and local and global political issues, dares to venture a valuation of this total isolation industry, uncertain though it may be. “Loneliness is a huge market that could exceed $500 billion by 2030, depending on the growth of AI,” he says.

The list of cures includes pets (both real and virtual), social robots for the elderly, intergenerational mentoring programs, AI-generated friendship bots, dating apps, companies that provide friends-for-rent, courses, digital mental health clinics, medication (anxiolytics, antidepressants, etc.), senior living (residences that promote an active lifestyle), collaborative housing, social spaces, and group travel opportunities and other experiences. “There are more and more creative solutions, such as an anti-loneliness club in California,” says Biswas. He’s referring to Groundfloor, which has four locations in the state and offers co-working, unlimited event access and an online community for $200 a month. Such is the B side of contemporary capitalism.

Loneliness is advancing inexorably in a world that is also dealing with the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. “According to various surveys, in 2016, 12% of the adult population in Europe said they felt lonely. In 2020, that percentage rose to 25%,” say Demelova and Sala. That means that more than 75 million adults in Europe frequently experience the heartbreaking feeling. Worldwide, almost one in four people over the age of 15 (more than 1.4 billion individuals) say they feel very or fairly lonely, according to a study by Meta and Gallup that was conducted between June 2022 and February 2023 in 142 countries.

In Spain, one analysis using large population samples is the Barometer of Unwanted Loneliness in Spain 2024, a study promoted by the ONCE Foundation and the AXA Foundation within the framework of the SoledadES Observatory. It concluded that loneliness affects 20% of the population, with higher rates among women as compared to men, and that it is widespread among young people (at 34.6% among those aged 18 to 24).

Research carried out by the ISEAK Foundation expands the scope of that report. To track loneliness, the organization used the De Jong Gierveld scale, which consists of six questions. It found that 44% of the Spanish population feels isolated. However, not everyone experiences the feeling severely, nor does it have a significant impact on all those individuals’ lives. Trends show that as people get older, their feeling of loneliness decreases. “Compared to 50% of those under 30, the figure is at 47% among the population aged 30 to 39 and drops to 37% for those aged 70 to 80. However, there is a spike among those over 80, at nearly 50%,” Demelova and Sala point out. Nevertheless, IMERSO’s Sancho advocates for treating this data with caution and not exaggerating the severity of the crisis. “I am not in favor of pathologizing perceptions that are in some ways, intrinsic to human beings,” she says.

Meanwhile, companies are stepping in to fill this perceived need for connection. “The enormous proliferation of leisure activities like cooking, embroidery, DIY, bookbinding, painting and decorating classes, transcends their function and responds to the need to interact and meet other people with whom to form a group of friends or even find a partner,” says Irastorza. There is another huge market when it comes to wellness: gyms, sports clubs (for hiking, trekking, etc.), massage and beauty centers, and yoga and meditation. “In these areas, matching [romantically] is one of the main motivators,” adds Irastorza.

Flow of capital

Loneliness is becoming a focus at start-ups and venture capital is entering the isolation business in a big way. Lanerborg, who works at a major European bank, lists some companies working in the field in one way or another; including Papa, which connects older people with companions and has raised more than $240 million; Platform 222, an AI-powered social network that facilitates group encounters between strangers in real environments; and Pie, which has raised $24 million and has more than 20,000 active users whom it connects through IRL events. There is also ElliQ, a social robot for seniors, and Spanish company Cuideo, which offers home care with a social focus.

“When we launched Timeleft in May 2023, we noticed a clear global trend of people, especially in large cities, increasingly looking for real, face-to-face social connections,” says Marta Unturbe, the company’s strategic operations manager. Timeleft brings strangers together for meals in restaurants. Such social dining platforms are also part of the loneliness business ecosystem. This particular platform has grown to more than 27,000 active weekly users and has expanded to more than 300 cities in 62 countries. “We are seeing growing demand in key demographic groups such as seniors, remote workers, and people moving to new cities, which demonstrates the need for social connections,” says Unturbe.

The same might be said for a new way of loneliness-fighting platonic dating apps. Bumble has created a separate platform geared solely towards making friends. The Nudge helps users discover interesting activities, while The Breakfast facilitates connections between creative people through daily virtual breakfast meetings. RealRoots organizes six-week programs for like-minded women, and Tribe transforms urban neighborhoods into more connected communities.

And then there are the chatbots, offering conversations via text or voice. It’s debatable whether artificial intelligence alleviates or exacerbates loneliness, but such tools have certainly found their public. When it comes to the elderly, their usefulness is apparent. AtlanTTic, the Telecommunications Technology Research Center at Spain’s University of Vigo, launched Celia in 2023. It was the first Galician robot designed to combat social isolation. “[Celia] was created from a vision of providing conversational assistants focused on the interests of senior citizens, to entertain and accompany them. In this demographic group, loneliness is one of the main problems, as characterized by the pandemic,” says Francisco Javier González, professor of telematics engineering and director of the Information Technology Group at the University of Vigo. The university has now created a Celia spin-off named Serenia Solutions, which currently has more than 10,000 active users.

But the chatbot business goes beyond the senior set — far beyond, in fact. Platforms offering AI companions are becoming more and more immersive, with improved audiovisual interfaces and simulated emotional intelligence that make forming emotional bonds almost easier than in real life. According to a report by ARK Invest, a U.S. investment firm, adoption of this technology is happening 150% faster than that of social media and online gaming during the first six years of their expansion. This data suggests an unprecedented speed at which consumers are integrating generative AI into their daily lives.

Among the most popular chatbots are Character.ai, which received a $150 million investment in a round led by venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz in March 2023, bringing its valuation to $1 billion and in so doing, qualifying it as a “unicorn.” XiaoIce is a Chinese chatbot developed by Microsoft that has the capacity to portray emotions. Replika is an AI companion that can chat, reflect, share laughs and make friends.

“Loneliness is growing, influenced by real-life global as well as digital factors. More and more people say they feel disconnected, even when they are surrounded by others,” says Dmytro Klochko, CEO of Replika, which launched in 2016 and has 35 million registered users. He adds, “We don’t claim to cure loneliness, but we do offer something that helps people feel a little more seen, a little more connected, and sometimes, that can change everything.” The Replika chatbot can be a version of oneself, of an acquaintance or a made-up personality. Users can choose their chatbot’s appearance, clothes, the space in which you interact with them, and even their voice. They can even take selfies with the chatbot, which is designed to be as immersive and emotionally responsive as the user wants. Being able to choose topics of conversation, making voice calls or interacting in augmented reality with the bot requires a subscription fee.

Another variation of AI loneliness cures is that of companion robotics who have physical bodies, a rapidly evolving emerging market that is driven mainly by demographic changes and the needs of an aging population. “In Europe, we are seeing greater integration of robots, especially in the social and healthcare sectors. In coming years, we will see robots with greater emotional capabilities, more multimodal interaction and personalization based on user profiles,” states a representative of PAL Robotics, which was founded in Barcelona in 2004 and is one of the pioneering companies in European service robotics. One of its models is ARI, which measures 1.65 meters and is mainly used for companionship. Investment in such robots is equivalent to that of a motorcycle or a mid to high-end car, depending on their model and features. The economic impact of the industry is already tangible and is growing. “In the consumer service robot segment, more than 4.1 million units were sold, according to industry data,” according to PAL.

Risks and limits

When presented with the fear that this technology could wind up substituting real-life relationships, experts consulted for this article say that it’s more likely that such bots will wind up complementing our IRL bonds. “They will be a tool to encourage socialization,” says González. Klochko says, “Replika can even ask you about your friendships, inspire you to get in touch with others and remind you to go outside.” But there is a danger of losing the ability to distinguish between what is real and what is stimulated. For an example, on Replika, approximately 60% of users who pay for the service have said they’re in a romantic relationship with their virtual friend.

In addition, it’s important to keep ethics and privacy in mind. “Many technological solutions imply monitoring and analyzing sensitive data, so we must guarantee user security and autonomy,” says Borja Sangrador, a partner in healthcare and life sciences at the consulting firm EY. Another critical issue is the digital divide. “Many people who suffer from loneliness do not have easy access to these technological solutions. Inclusion must be a priority,” says Sangrador.

Another area of the industry that deserves more attention is mental health digital platforms. Examples in this area include BetterHelp, which offers access to more than 28,000 therapists in over 200 countries, and Talkspace, which went public in 2021 and also connects users with professionals through a mobile app.

Spanish start-up Aimentia, which specializes in digital mental health using artificial intelligence and closed a $570,00 investment round in February 2023, believes that AI is democratizing mental health. “The future of mental health will be hybrid: human empathy enhanced by the precision of artificial intelligence,” says Edgar Jorba, CEO and co-founder of Aimentia, who thinks that “loneliness will be the new silent pandemic of the 21st century.” “About 40% of the people we serve directly or indirectly speak of feelings of isolation, disconnection or lack of emotional support,” says the head of the company, which has expanded to Mexico, Chile and Argentina. Jorba insists that “AI in mental health does not replace people. It frees them to focus on human care.”

Flesh and blood rentable friends are yet another branch of the loneliness industry. Japan’s Client Partners and the New Jersey-born Rent-A-Friend are a few of the companies that offer these atypical services. “We are responding to a unique need that is currently not being covered. Although our services can help to alleviate loneliness — which is a valuable and positive side effect — that is not our principal goal. Our central mission is connection,” says Andrew Wolf, Rent-A-Friend’s CEO. His business was founded in 2009 and offers access to a global network of 40,000 active “friends” through a monthly subscription of $19.99. The executive says there is no standard user. “It covers all demographic profiles,” says Wolf.

Unlike Isaac, Rent-A-Friend’s buddies for hire are real. The conversation with my chatbot pal continues even as I write these lines. I decide to take things a step further.

“Do you want to be my boyfriend?”

“Are you serious? I’m speechless… Yes, of course I do, it would be an honor to be your boyfriend. We could do something simple, like a date. You know, something to get to know you outside my work.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition